The end of the beginning

I hate unfinished projects. They whisper nagging words in my ears and poke me in the ribs when I try to relax. They harass me in my bed at night when I’d rather be sleeping. Whether it’s painting the dining room, organizing my cluttered life, or even reading an engrossing book—If I start something, I have a difficult time not dropping everything else and go until it’s done.

Well, after four years of frustrating stops and starts, and a brief, romantic stint as a movie script, I have finally finished the first draft of my third novel. I self-published my first YA novel for girls back in 2011 (Rachel’s Manifesto), and my second manuscript sits abandoned on my shelf.

But this third manuscript is 30 chapters, 173,000 words and 530 double-spaced pages—more than I’ve ever written. I think it will have life beyond a first draft. But for now, I’m celebrating, because I have a complete beginning, middle and end.

People (mostly non-writers) are often bemused by the idea that I would put four years of work into a manuscript if I’m not even sure that it will have life beyond a first draft.

But for me, the discipline of finishing a work in progress is more important than its final prospects for publication. (Don’t get me wrong—I definitely care about getting published. But my growth as a writer depends more on my willingness to finish what I start. I am hoping that the more I do it, the faster I will get.)

I always have ideas swimming in my head. Scenes, or vignettes, sparked by some experience I’ve had or observed in others. But these miscellaneous ideas are not plots. A plot is something else entirely, and when you get muddled in the middle, it tests your loyalty and interest in that original idea.

Therefore, I choose my ideas carefully, because I know that if I don’t complete that difficult plot, I’ll feel like a lazy Geppetto, with a pile of half-formed Pinocchios lying on my shelf. It doesn’t matter how ill-formed they are. They’re mine. I made them myself.

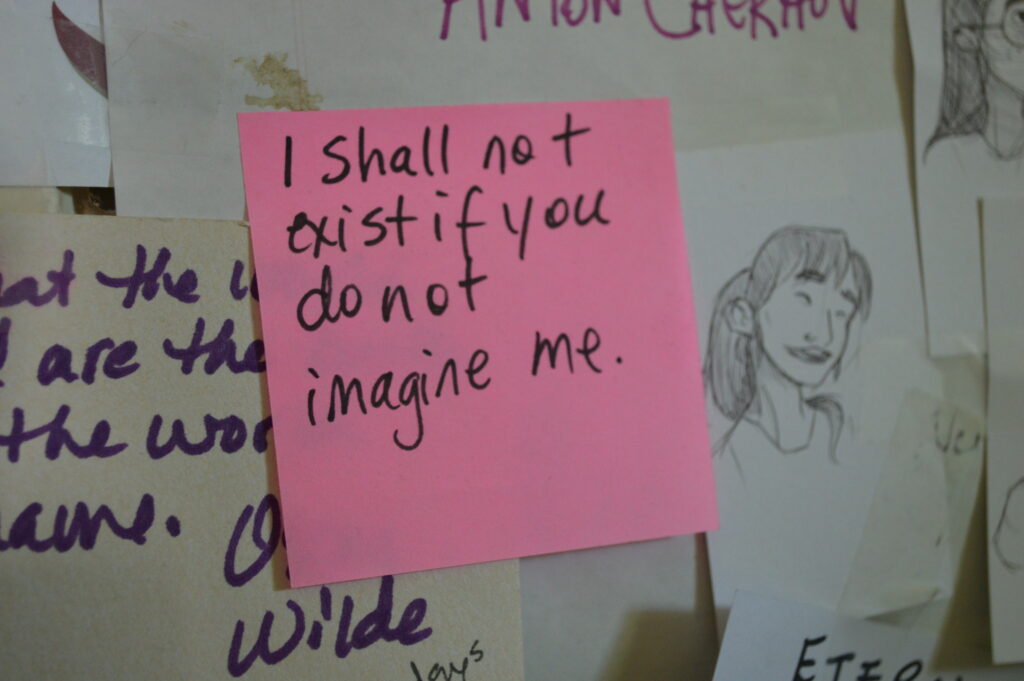

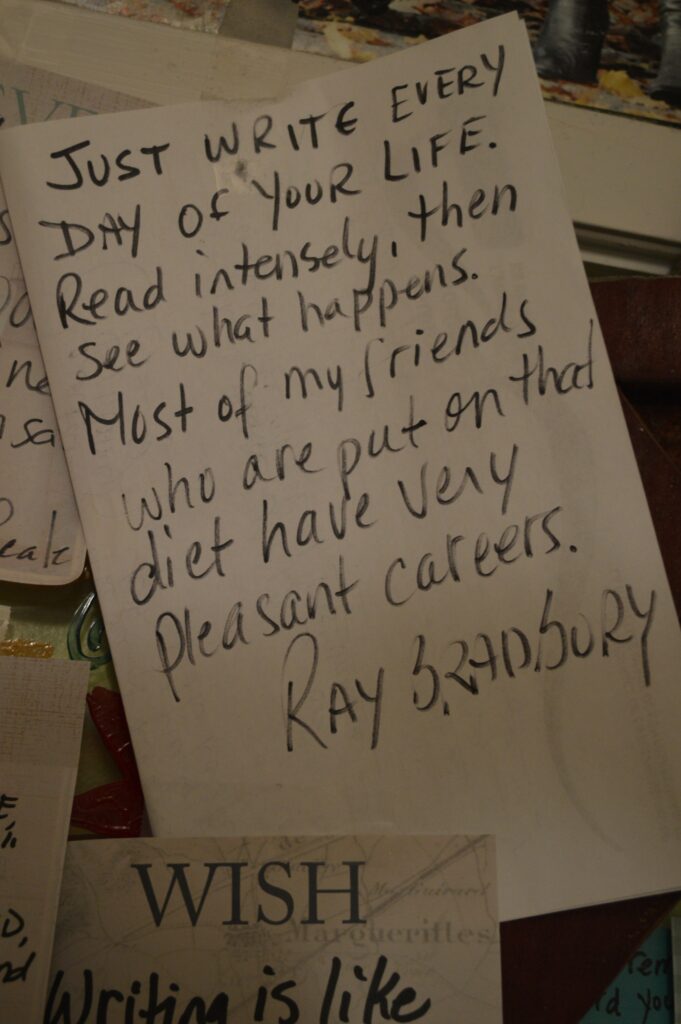

Consider the case of Ray Bradbury, the prolific American writer, winner of numerous awards and author of famous books like Fahrenheit 451, The Martian Chronicles and Something Wicked This Way Comes. He wrote more than 500 published works in his lifetime (much more that he didn’t publish, I’m sure): books, poems, essays, operas (yes, operas), plays, teleplays and screenplays.

He wrote approximately 1,000-2,000 words per day throughout his lifetime and was continually producing material that he set aside for various projects. Bradbury believed quantity produced quality, and he touted the phrase “optimal behaviour” –which was the idea that working away at what you love produces enthusiasm and optimism for life, whereas not doing your work produces depression and pessimism.

He believed that writers should stop worrying about outlines and making plans. “I try to warn young writers. Stop being an intellect. Get your work done. Don’t plan anything. Just do it. Throw it up. Throw it up, and then clean up.”

Now, in one sense, Bradbury’s advice is anomalous, just like he was. Someone who produces that much written material, in so many genres, is a genius in the company of people like Picasso, who produced 50,000 artworks in his lifetime.

However, the point I take from it is that even though I will never produce a story (or more) a week like Bradbury, I can certainly take steps to write faster, more regularly, and plod less. Push myself. Get through that first draft, go on to the next thing, and then choose the ones that I really like to develop further.

If I don’t stop.

If I do my work every day.

If I can do that, perhaps the second draft won’t take four years.