Regarding politics and the media

Two years ago, I watched an episode of the Munk Debates, which was held live at Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto on November 30, 2022, entitled “Be it Resolved, Don’t Trust Mainstream Media.” I sent this note directly to the Munk Debate producers, at the time, but I thought it was worth editing and posting to my blog, given the – ahem – rather consequential event happening south of the border tomorrow, November 5. No matter who wins the US election, much is made of the lack of objectivity on the part of the media in most matters of public interest, not just politics.

This two-year-old debate featured Douglas Murray (Author and columnist, The Spectator), Mike Taibbi (Author, Substack), Malcolm Gladwell (Author and columnist, The New Yorker) and Michelle Goldberg (New York Times, NBC) and I originally watched it when it appeared in my YouTube feed shortly after the live event. If you missed it, you can watch it here.

At the time, I would have wished for at least one more Canadian other than Gladwell to be featured as a debater, and I would have wished for more references to examples of Canadian media, but overall I was pleased to hear a proper public debate on this subject – and I’d love to hear more.

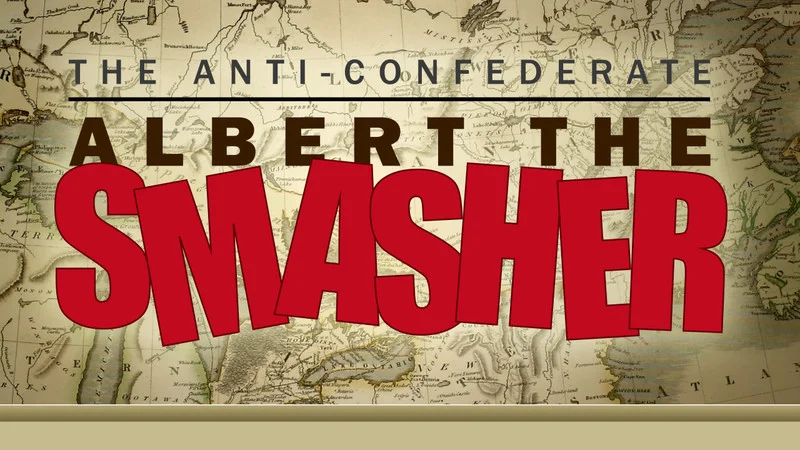

I’d like to make a point (and maybe a hypothesis) that I gleaned from some historical research I did a few years ago while researching a New Brunswick historical politician (and strong anti-confederate) named Sir Albert James Smith. My husband and I did an animation on his life in honour of Canada’s 150th anniversary celebrations seven years ago. You can watch the 20-minute video here, if you like.

In the course of research, I read a thesis by a Canadian historian named P.B. Waite, who delved into media publications as well as the correspondence of politicians and British governors throughout all the provinces in the leadup to Confederation, to track the mood of the country at the time. The thesis is called THE LIFE AND TIMES OF CONFEDERATION 1864-1867 – Politics, Newspapers, and the Union of British North America, by P. B. WAITE, University of Toronto Press, 1962.

He noted that back then, newspapers were plentiful, and that the political patronage of newspapers in return for favourable reporting was absolutely the norm. “The relationship between newspapers and politics was often a matter of loyalty to friends, party, or principle: it was also, sometimes, a matter of dollars and cents. Newspapers had their principles, but newspapers, and principles, could be bought and sold. For this reason, if for no other, newspapers must be used with care. They were too often ready to trim to a fresh wind, or to alter their course, for due consideration, to a new bearing. And the aim of their editorials was persuasion.”

After that long introduction, my point: Given this beginning, when did journalism turn into a profession that was actually neutral and trustworthy, populated by journalists who wouldn’t take graft to publish a story that a politician or a company wanted them to tell? Was it sometime in the twentieth century? We could say that Waite’s quote was illustrating an industry that was in its infancy, and it gradually matured into what we all expect it to be – objective – the fourth estate, which questions everything on the public’s behalf, and holds public officials and institutions to account. When I was growing up, I think we more or less had that, even though I don’t think journalists or large media institutions can ever be totally neutral – they’re humans, after all. That is where reading widely comes in.

Public trust in the institution of media is now crumbling away, I suspect not without good reason (see Munk video).

My hypothesis is that with the rise of the Internet and social media, citizen journalism via YouTube channel, Substack, etc., we are returning to those early days when information is everywhere, and plentiful, and the aim is persuasion. This technological Wild West has completely blown up the media business model, too.

There is no way for a government – I’m looking at you, Liberals – to control the amount or kinds of information available (whatever they deem as misinformation or disinformation) as a government without becoming despotic.

If we want to live in a free society, the government must instead take their hands off the information taps. People must learn to separate truth from error on their own.

I’m not stupid, and I doubt you are, either. But I think our government thinks we are. They feel the need to intervene, for all kinds of good reasons, I’m sure. But this is a dangerous trend.

For the average citizen, this is not about stupidity – it’s about being lazy. In our 30-second Instagram Reel world, our attention span is dropping and our prickliness is rising.

I wonder how Albert Smith’s contemporaries handled the smorgasbord of information that was more or less (or not) true, or at least riddled with persuasion. Nevertheless, we survived 160 years since then, so the public must have seen through it somehow. We adapted.

And so, rather than scold you, dear reader, I will focus on myself and say that I am aware of the danger of focusing on talking points that support what I already think is true. We all carry ideologies, if we are the least bit political and/or religious (I am both). It’s impossible to live without biting down on some guiding principles. But I think that ideology needs to be supported by objective truth, which comes from reading widely.

I’m sure that among all the dross on the internet, the gold is out there. We just have to be willing to dig through the dross to find it.